SOFTWARE ACQUISITION GOLD PRACTICETM

GOAL-QUESTION-METRIC (GQM) APPROACH

FOCUS AREA: PROCESS - MEASUREMENT

Definition and Summary: A goal-driven method for developing and maintaining a meaningful metrics program that is based on three levels, Goals, Questions and Metrics. The approach uses metrics to improve the software development process (and its resulting software products) while maintaining alignment with organization business and technical goals.

The consensus of a recent GAO Report on Defense Acquisitions (GAO-04-393), published in 2004, was that stronger management practices are needed to improve DOD’s software-intensive weapons programs. The report goes on to state that the success (quality software product, on time and within budget) of leading software companies is attributable to creating a manageable evolutionary development environment, using disciplined processes, and collecting and analyzing meaningful

metrics to measure progress. This GQM Gold PracticeTM provides practical guidance for implementing the GQM approach to

measurement in order to establish and use meaningful metrics, (which are well aligned with the goals of the organization), to help mitigate risk, track progress and support improvement initiatives.

.

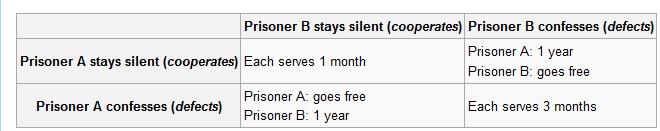

GQM is a top-down approach to establish a goal-driven measurement system for software development, in that the team starts with organizational goals, defines measurement goals, poses questions to address the goals, and identifies metrics that provide answers to the questions. GQM defines a measurement model on three levels as illustrated in the figure below:

GQM can be applied to all life-cycle products, processes, and resources, and is well aligned with the organizational environment. The approach was developed by Dr. Victor Basili and colleagues during the 1980s in conjunction with their work at the NASA Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL), was refined during the 1990s, and now, serves as the foundation framework for many measurement initiatives. It is an appropriate means to achieve reliable empirical data and knowledge about the organization’s software practices to drive systematic process improvement. In that context, it is particularly useful for the following purposes:

• Understanding and baselining an organization’s software practices

• Guiding and monitoring software processes

• Assessing new software engineering technologies

• Evaluating and certifying improvement activities

Although the primary focus of the practice is goal-driven metrics definition, the approach also addresses data collection, analysis and interpretation and packaging experiences for use in future initiatives. These activities are equally as important as defining the metrics because they guide how the data is actually used.

Some effective practices for implementing GQM, discussed in detail in the document, are:

• Get the right people(all levels of developers) involved in the GQM process

• Set explicit measurement goals and state them explicitly

• Thoroughly plan the measurement program and document it (explicit and operational definitions)

• Don’t create false measurement goals

• Acquire implicit quality models from the team

• Consider context

• Derive appropriate metrics

• Stay focused on goals when analyzing data

• Let the data be interpreted by the people involved

• Integrate the measurement activities with regular project activities

• Do not use measurements for other purposes

• Secure management commitment to support measurement results

• Establish an infrastructure to support the measurement program

• Ensure that measurement is viewed as a tool, not the end goal

• Get training in GQM before going forward

ANTICIPATED BENEFITS OF IMPLEMENTATION:

Some benefits of this practice that were identified in the PERFECT project [PERFECT,1997] include:

• Achievement of improvement goals

• Financial gains

• Increased capability to perform improvement initiatives

• Improved group synergy

• Increased quality awareness and Quality Assurance (QA) involvement

DESCRIPTION OF THE PRACTICE:

SUMMARY DESCRIPTION

The Goal-Question-Metric (GQM) Approach is a paradigm for developing and maintaining a meaningful metrics program that supports:

· Metric alignment with organization business and technical goals

· Software process improvement

· Risk management

· Product quality improvement

This Gold Practice document describes the basic concepts of the GQM paradigm and addresses key aspects of its implementation. The practice focuses on measurement of goals and supports interpretation of measurement results relative to those goals. Although GQM originated as a measurement methodology for software development, the basic concepts of GQM can be used anywhere that effective metrics are needed to assess satisfaction of goals.

GQM can be applied to all life-cycle products, processes, and resources, and is well aligned with the organizational environment. The approach was developed by Dr. Victor Basili and colleagues during the 1980s in conjunction with their work at the NASA Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL). It was refined during the 1990s, and now, serves as a foundation framework for many measurement initiatives.

Benefits of GQM

Although the direct benefit of GQM is establishing meaningful metrics, when GQM is applied within the context of systematic process improvement, it is particularly useful for the following purposes:

• Understanding and baselining an organization’s software practices

• Guiding and monitoring software processes

• Assessing new software engineering technologies

• Evaluating and certifying improvement activities

In Europe, between 1993 and 1996, several industries formed a consortium with the goal of initiating measurement-based software process improvement. That initiative, called project “PERFECT” (Measurement Based Improvement of Software Processes), noted the following benefits from using the GQM approach [PERFECT 1997]:

• Achievement of improvement goals

• Increased quality awareness and Quality Assurance (QA) involvement

• Increased capability to perform improvement initiatives

• Improved group synergy

• Financial gains

GQM Basics

The open literature typically describes GQM in terms of a six-step process where the first three steps are about using business goals to drive the identification of the right metrics and the last three steps are about gathering the measurement data and making effective use of the measurement results to drive decision making and improvements. In a recent seminar, [Basili 2005] Basili described his six-step GQM process as follows:

1. Develop a set of corporate, division and project business goals and associated measurement goals for productivity and quality

2. Generate questions (based on models) that define those goals as completely as possible in a quantifiable way

3. Specify the measures needed to be collected to answer those questions and track process and product conformance to the goals

4. Develop mechanisms for data collection

5. Collect, validate and analyze the data in real time to provide feedback to projects for corrective action

6. Analyze the data in a postmortem fashion to assess conformance to the goals and to make recommendations for future improvements

As illustrated in the figure below, GQM begins by identifying measurement goals (conceptual level) that support (are aligned with) business goals. The team (project managers, development team, customers, or other stakeholders) then poses questions (operational level) to further clarify and refine the goals as well as capture the variation of understanding of the goals that exists among the stakeholders with respect to their notions of quality and the environment that will impact goal attainment. The team then identifies metrics that will provide answers to the questions (Quantitative level). What distinguishes GQM from other measurement paradigms is the hierarchical tree structure used to maintain the relationships among goals, questions and metrics.

Once appropriate metrics are identified, the last three steps of the GQM process address how to implement the metrics

program in a way that ensures the focus will remain on goal attainment. Basili and other GQM experts stress the importance of planning data collection mechanisms and planning how the resulting measurement data should to be organized and presented

in order to maximize its value to the stakeholders who will interpret the results in relation to the goals. The literature notes that when measurement programs fail, the primary cause of failure is often a lack of attention to how the measurement results will be used.

Implementing GQM

GQM can be applied at the strategic level of an organization, or the project level, or at both levels concurrently. When applied at the strategic level, the measurement data consists of results from targeted pilot projects providing the feedback to strategic level planners for decision making relative to product and process strategies.

Organizations often use a phased approach for implementing GQM that integrates GQM-related activities (derived from Basili’s GQM process) with project planning and management activities. The phases are GQM Planning, Definition, Data Collection and Interpretation. A more extensive explanation of the phased approach, and how it relates to Basili’s six step process, is provided in the body of this document.

Some effective practices for implementing GQM, described in detail in the body of this document, are:

• Get the right people(at all levels of developers) involved in the GQM process

• Set and state explicit measurement goals and state them explicitly

• Thoroughly plan the measurement program and document it (explicit and operational definitions)

• Don’t create false measurement goals

• Acquire implicit quality models from the team

• Consider context

• Derive appropriate metrics

• Stay focused on goals when analyzing data

• Let the data be interpreted by the people involved

• Integrate the measurement activities with regular project activities

• Do not use measurement for other purposes

• Secure management commitment to support measurement results

• Establish an infrastructure to support the measurement program

• Ensure that measurement is viewed as a tool, not the end goal

• Get training in GQM before going forward

DETAILED DESCRIPTION

The Goal-Question-Metric (GQM) practice focuses on following the GQM paradigm for establishing a metrics program to support software development and maintenance. Organizations typically implement GQM as part of an overall software

process improvement initiative, but it is not limited to that role. The basic concepts of GQM can be used anywhere that effective metrics are needed to assess satisfaction of goals. It can even be used by individual members of a project team to focus their work and assess their progress toward achieving their specific goals.

GQM can be applied to all life-cycle products, processes, and resources, and is well aligned with the organizational environment. The approach was developed by Dr. Victor Basili and colleagues during the 1980s in conjunction with their work at the NASA Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL). It was refined during the 1990s, and now, serves as a foundation framework for many measurement initiatives.

GQM BASICS

In one of his most recent professional development seminars [Basili 2005], Basili defines the GQM process as follows:

1. Develop a set of corporate, division and project business goals and associated measurement goals for productivity and quality

2. Generate questions (based on models) that define those goals as completely as possible in a quantifiable way

3. Specify the measures needed to be collected to answer those questions and track process and product conformance to the goals

4. Develop mechanisms for data collection

5. Collect, validate and analyze the data in real time to provide feedback to projects for corrective action

6. Analyze the data in a postmortem fashion to assess conformance to the goals and to make recommendations for

future improvements

The first three steps are about establishing a goal-driven measurement program where the identification of goals triggers the identification of appropriate metrics. The remaining steps are about collecting and using the measurement results for better decision making. Later in this document, we will discuss how the process is implemented as a phased approach that is integrated with project planning and project management, and show how the process can be implemented at various levels within the organization.

Figure 1 presents a high-level visual synopsis of the definition phase of the GQM paradigm, illustrating the outputs of first three steps of Basili’s GQM process, the hierarchy of goals, questions, and, ultimately, meaningful metrics.

This part (the first three steps) of Basili’s GQM process, often called the definition phase of GQM, provides the process structure for migrating from concepts to meaningful metrics that, when implemented, quantify the goals and provide meaningful data for decision-making. Goals identify what we want to accomplish; questions, when answered, tell us whether we are meeting the goals or help us understand how to interpret them; and the metrics identify the measurements that are needed to answer the questions and quantify the goal.

s illustrated in Figure 1, the mapping among goals, questions and metrics is not one-to-one. A single measurement goal may apply to multiple business goals and vice versa; for each goal, there can be several questions and the same question can be linked to multiple goals as appropriate. For each question, there can be multiple metrics, and some metrics may be applicable to more than one question. Adherence to, and preservation of, this hierarchical structure helps ensure that the measurement program focuses on the right metrics and that we avoid extra work associated with collecting metrics that are not really needed.

The remaining steps of Basili’s GQM process (relating to data collection and analysis for decision-making and for future recommendations) are actionable only when appropriate definition of metrics has occurred. Goal-driven metric definition, using the goal-question-metric process, is what separates GQM from other measurement methodologies. Thus, this document emphasizes the initial steps of Basili’s GQM process because they provide the foundation for the remaining steps of the process.

A primary tenet of GQM, not usually evident in illustrations of the GQM paradigm, is that stakeholders need to be involved throughout the process in order for it to be successful. Basili, and others [Basili 2005, PERFECT 1997], advocate for planning the implementation of GQM to ensure that those with a stake in any part of the process actually participate to ensure their knowledge is considered, that they understand their contribution (role) in the process, and to promote their buy in and acceptance of the measurement program. Those who implement GQM may use a variety of approaches to ensure the appropriate level of participation. The key message is that the measurement program should be planned and implemented from within the organization or project, rather than be outsourced. However, the experts agree that it is helpful to have a consultant (GQM expert) work with the team or organization in the initial stages to ensure that the principles of GQM are implemented, and to transition those principles to key people within the organization.

GQM PROCESS DETAILS

This section provides details about each of the six steps of Basili’s GQM process.

Step 1 - Establishing Goals

In his recent DACS course [Basili 2005] Basili lumps all goal setting into the first step of his GQM process description because he is teaching organizational leaders what the organization must do to build core competencies in software development (applying GQM at a strategic level). Others [PERFECT 1997] suggest that the GQM process begins with establishing measurement goals using previously defined business goals as a driver. The essence of the step is:

· There are two types of goals --- business goals and measurement goals

· Business goals drive the identification of measurement goals

Sometimes, it is difficult to distinguish between a business goal and a measurement goal; they may not always be mutually exclusive. What is important is that the driving goals originate from the group or organization which is responsible for the broader scope of a software initiative, the business environment in which the initiative occurs, rather than from within a particular project. It is not important whether the business goals are developed under the umbrella of GQM, or as a function of strategic planning. Business goals must exist; they must be identified and be the focus for establishing the measurement goals. Without them, the measurement program has no focus. Without this alignment, it is unlikely that implementing the rest of GQM will have a significant impact. When business goals exist, then multiple projects or sub-groups within an organization have a basis for identifying the measurement goals relating to their role or scope of influence within the organization.

The goals at the top of the GQM tree (see Figure 1) are the measurement goals that are the outcome of step 1 of the GQM process. They are conceptual, not quantitative. They are quantified by their linkage to questions and metrics as noted in the mapping. Some examples are provided later in this document to illustrate this point (see Figure 3).

Basili and his followers express GQM goals (measurement goals) using five facets of information to define what the measurement should accomplish in precise terms. Each GQM goal statement explicitly contains these facets:

· Object: The product or process under study; e.g., testing phase or a subsystem of the end product

· Purpose: Motivation behind the goal (why); e.g., better understanding, better guidance, control, prediction, improvement

· Focus: The quality attribute of the object under study (what); e.g., reliability, effort, error slippage

· Viewpoint: Perspective of the goal (who’s viewpoint); e.g., project manager, developer, customer, project team

· Environment: Context or scope of the measurement program; e.g., project X or division B

Some implementations of GQM use a table-formatted template for goal definition (see Table 1). The left column identifies the five facets of information and remains constant on the form; the right column changes for each goal defined [van Solingen

1999b].

Step 2 – Generating Questions

The purpose of Basili’s Step 2 is to clarify and refine the measurement goals, moving from a conceptual level to an operational level by posing questions. By answering the questions, one should be able to conclude whether a goal is reached. Questions help identify interpretations of the goal that may exist among the stakeholders as well as constraints imposed by the environment. Typically, at the project level (or perhaps for a group of related projects), conceptual measurement goals are identified relating to product quality, process, resources, or the environment. The project team then identifies questions that the team (individually or collectively) feels should be asked to capture various perspectives of the goal and address whether the goal is being met. These questions would typically get at all of the nuances and perceptions relating to the goal, addressing both perceptions of quality and the context or environment in which the object will evolve. This is essentially a process of stakeholders converging on a common understanding and interpretation of the goal at the appropriate level of abstraction. In other words, the individual project managers and software engineers provide their perspective of what the goal means in the given environment. They do this by posing questions and responding to them with their metrics. Figure 3 provides a simplified example illustrating some of the questions that might emerge for the specified goals.

On the surface this step may appear to be trivial, and for some goals that may be the case, but GQM experts [Basili 2005, van Solingen 1999b, PERFECT, 1997] and implementers have found that getting the right level of abstraction for GQM questions can be difficult. If questions are too abstract, the relationship between the metrics and the question may be muddied. If they are too detailed, it becomes more difficult to get a clear interpretation of the goal. In many instances, particularly where the purpose of the goal is to understand or characterize the process or product, questions may need to be broken out into many sub-questions to drive appropriate identification of metrics. The implementing organization may tailor this step of the process as needed to ensure that the level of questioning is sufficient to drive the identification of the right metrics. Some excellent examples of ensuring the appropriate level of questioning are provided in the Case Studies section of van Solingen’s book [van Solingen 1999b].

In some implementations [van Solingen 1999b], a GQM team interviews the stakeholders (members of the project team) individually to capture their perspectives of the goal (their questions) and to have them formulate expected answers as hypotheses. These hypotheses make explicit the current knowledge that is in the minds of the team members thus, forming a baseline for later analysis of metrics. Comparing actual results with these hypotheses during the interpretation phase of GQM increases the learning effect from measurement.

Step 3 – Specifying the Measures

Step 3 is about examining how the questions could be answered, moving from the qualitative (or operational level) to a quantitative level. Once goals are refined into a list of questions (GQM process step 2), metrics need to be defined that provide all the quantitative information to answer the questions in a satisfactory way. Stakeholders, those directly involved with the object of the goal, must be directly involved in the metric identification step as well as the Question step. Direct involvement of these stakeholders minimizes ambiguities and false assumptions and contributes to the overall consistency and completeness of the metrics identification.

In this context, the term metric is loosely defined; it can mean a base measure, a derived measure, a composite or aggregate of measures, or, what some would call, an indicator. The level of definition depends on the scope of the goal and the environment of the GQM implementation. Further details are provided later in the section describing GQM implementation. Figure 3

provides a simple example of how GQM would derive metrics for two goals. It shows some of the essential questions that would emerge, and some of the metrics that might be identified.

The diagram is intentionally oversimplified in order to convey the notion of how one gets from a conceptual level goal to the right quantitative data that renders the goal measurable. It also conveys the multiple mapping of metrics to questions and questions

to goals.

A refined GQM goal statement for Goal 1 in Figure 3 might read as follows:

Analyze: Change request processing

For the purpose of: Improvement

With respect to: CR processing cycle time

From the viewpoint of: The project team

In the context of: The current project timeframe

Note a distinction between the metrics that are defined and the data elements that support them. The metric is at a more abstract level than the actual data items and measurements that need to be collected to provide the correct data for preparing the metric.

Step 4 – Preparing for Data Collection

Once the metrics are identified, one can determine what data items are needed to support those metrics, and how those items will be collected. The metric provides insight regarding how the data needs to be organized in order to be meaningful to the viewer/recipient of the information. A significant amount of planning is necessary to provide the detailed procedures for data collection that support the identified metrics. Most projects accomplish this detailed planning by preparing a Measurement Plan that includes at least the following [van Solingen 1999b]:

· Formal definitions of direct measurements

· Textual descriptions of direct measurements

· All possible outcomes (values) of the direct measurements

· The person (role) that collects each direct measurement

· The moment in time (or frequency) when the direct measurement should be collected

· The medium (tool or form) that should be used for collecting the measurement

The plan also defines and describes all types of data collection forms and automated data collection tools that should be used. It addresses the question of how the data can be collected most efficiently and effectively and to whom it should be delivered.

Referring to the example in Figure 3 of Change Request processing time, one cannot assume that all stakeholders have the same understanding of what constitutes CR processing time. Does it begin when the CR is first documented, or after it is diagnosed and categorized for action? When is processing considered done? Which CRs are included for averaging --- only closed out CRs, or also those on hold? The Measurement Plan anticipates and addresses such questions.

Once a plan is developed, the measurement procedures need to be tested and validated before implementing the program. Exercising the forms and procedures during a trial period will reveal flaws that can subsequently be corrected before full-scale implementation of the measurement program begins, or before adding the new procedures and data to an existing program [van Solingen 1999b].

In addition, it is important to train individuals involved in data collection to ensure that they understand why the data is needed, how it is going to be used and how their action contributes to the overall validity of the data collection process.

Step 5 – Collecting, Validating and Analyzing the Data for Decision Making

This step presumes that data collection follows the procedures pre-defined in the Measurement Plan. It is often a continuous (or periodic) process rather than a one-time activity. However, it is only a means to an end. Data collection is a worthless process if one does not do anything with the data. The focus needs to be on preparing the data for optimal usage. Regardless of the collection medium, data needs to be validated before it is used for analysis.

Recently a Project Manager told the DACS a story about a group of developers responsible for maintaining an application that was particularly volatile. Each time they fixed a problem they entered a “1” in the Problem Report (PR) form field that asked for actual time spent on the fix. From their perspective, this was an irrelevant field because nothing was ever done with the data. They were very busy with a backlog of PRs and it took time to accurately estimate the time to fix each problem. Their Manager, who knew that many PRs required extensive time to fix, showed them a request for additional staff that had been denied based on a report of staff utilization that showed a graph of average time per PR, clearly demonstrating that the current staff was underutilized. Once the staff understood the significance of that data item, what decisions it affected, and that it was not measuring their personal performance, they started entering their estimates of time appropriately and the manager began to get valid data for his management purposes.

Automation can assist, but it cannot replace all forms of data collection and validation. The key is to minimize the overhead imposed on the people who are required to provide data while ensuring that they understand the significance of their data collection effort. Validation consists of checking the data collected for correctness, completeness and consistency. Completeness is the most significant data collection problem. What does one do with a form that is only half completed? How does one ensure that all instances of data are actually captured? These, and similar questions, need to be addressed in planning the measurement program so that there is a proper course of action available to those people tasked with validating.

As the story about the maintenance staff showed, leaders need to reinforce the purpose and value of data collection to promote better data collection quality. A significant part of the validation process is checking validity as close to the data source as possible and taking immediate corrective action for invalid data.

Once validated, it is important to store the measurement data in such a way that it can be accessed for varying analysis and reporting purposes. Because of the sheer volume of measurement data needed for all but the smallest of projects, it is useful to develop and use a measurement support system that contains a database for the storage of the metric data and tools for analysis (spreadsheets) and presentation. Flexibility and accessibility are the most important features of such a system.

Analysis is about organizing the data and preparing the metrics for presentation to the stakeholders to address the questions pertaining to the measurement goal. Typically, a GQM team, together with the project team, develops an analysis plan as soon as they know what metrics are needed. The plan details how the data should be organized, what presentation formats are needed, who will review the data and when. Developing the analysis plan often helps with decisions about data collection.

Basili [Basili 2005] uses the term analysis to mean both analysis and interpretation, but some implementers of GQM make a distinction between the two terms, primarily, to assert that the analysis can be done by a GQM team (measurement expert), but the interpretation must be done by the project team who are the owners of the measurement goals.

Some form of feedback is required to communicate measurement results to the appropriate stakeholders. These sessions are focused on the measurement goal and reviewing the measurement results to answer the questions posed in step 2 of the GQM process. The project team can then decide on corrective action when progress toward goals is not deemed adequate.

Analysis and interpretation is an iterative step typically integrated with the progress reporting cycle of a project.

Step 6 – Analyzing the Data for Goal Attainment and Learning

The last step in Basili’s GQM process is about looking at the measurement results in a post-mortem fashion to assess goal attainment and also to determine lessons learned and what might be valuable to pass on to future projects.

When GQM is implemented to support an organization-wide improvement process, the experiences and lessons learned from each implementation are packaged in the form of policies, procedures and best practices, to support future projects and improvement initiatives and to help the organization achieve greater leverage from its measurement program.

IMPLEMENTING GQM

Describing GQM in terms of a six-step process (see previous section titled GQM Basics) tends to convey it as a strictly sequential process, but that is not the case when GQM is actually implemented. Van Solingen [van Solingen 1999b] and others assert that implementation of GQM should be viewed in terms of phases of activities that are integrated with project planning and management and have dependency relationships with each other. Although they embody Basili’s GQM process, the focus of the phases is on the planning and implementation details needed to make GQM a reality within an organization. Solingen’s phases are named as follows and their relationship to each other is illustrated in Figure 5:

· GQM Planning: deals with the logistics of implementing GQM and key plans that need to be documented. This phase, therefore, touches steps 1 -5 of Basili’s process.

· Definition: focuses on using the GQM method to derive meaningful metrics. It encompasses the first three steps of

Basili’s six-step process.

· Data Collection: addresses planning for and executing data collection activities to obtain the data needed for the defined metrics. This phase addresses steps 4 and 5 of Basili’s process.

· Interpretation: Addresses preparing the measurement data in ways that facilitate analysis and interpretation of results relative to the pre-defined goals and actually doing the analysis and interpretation. This phase implements steps 5 and

6 of Basili’s process.

GQM Planning and Definition Phases

It takes a significant amount of planning to ensure that data collection and analysis are in fact coordinated with and actually address the defined measurement goals. Therefore, GQM needs to be integrated with, rather than separated from, project planning. The overall Project Plan specifies, that the GQM method will be utilized, and that GQM planning activities will occur. The GQM Planning phase oversees the implementation of GQM within the context of the project. It does not precede all other phases, but rather, is intermingled with them. Initially, the GQM planning phase establishes how the Definition phase will be implemented and who will be involved; then Definition occurs. Then GQM planning uses the output of the definition phase as a basis for the planning of data collection mechanisms and for analysis and interpretation. GQM planning thus provides documentation that serves as a guide for other phases of GQM, and provides the necessary integration with project planning. That is why the Planning phase block in Figure 5 stretches across the remaining phases.

Artifacts of the GQM Planning phase include, but are not limited to, the following documents:

(1) GQM Plan: As illustrated in Figure 5, the Definition phase consists of identifying measurement goals, posing questions, and identifying appropriate metrics. The GQM plan is a document that contains each measurement goal and its corresponding breakdown into questions and metrics, thus preserving the relationships of goals to questions to metrics. This document provides the foundation for progressing through the other phases of GQM, just as a requirements document provides the foundation for the activities of a development effort. The GQM plan contains the output from the first three steps of Basili’s GQM process [Basili 2005] described earlier.

(2) Measurement Plan: The GQM planning phase, additionally, includes developing a specific Measurement Plan that defines the actual base measures needed to generate the metrics defined in the GQM plan and establishes the detailed procedures for collecting the measurement data and generating the identified metrics. It should address what data is collected, how it is to be collected, by whom, and when. The Measurement Plan includes a description of the media needed to report, collect, and validate data. It serves to guide the activity of the Data Collection phase. Developing this plan is part of step 3 of Basili’s GQM process.

(3) Analysis Plan: The GQM Planning phase also encompasses developing an Analysis Plan that focuses on how to analyze, aggregate, and present the collected measurement data in ways that are meaningful to the stakeholders. What the project manager needs to see is different from what the Vice President needs to see and from what the Quality Assurance manager needs to see. The plan sets the stage for the Interpretation phase of GQM by providing guidance on how the information needs to be organized to facilitate its use and ensure that the focus remains on the goals. Basili’s process description does not specifically mention preparing this plan, but he implies (or perhaps assumes) that one makes a plan before one does analysis. It is likely to be considered part of Basili’s steps 4 or 5 that address developing data collection mechanisms and analyzing the data. The important point is that the planning for analysis and interpretation should be done prior to data collection so that it is clearly tied to the goals and does not fluctuate depending on the actual data values collected. The Analysis plan defines the appropriate level of abstraction for the presentation of the data.

Data Collection Phase

The Data Collection phase includes collecting the measurement data according to the Measurement Plan and preparing it for analysis in accordance with the Analysis Plan. This phase is covered by Basili’s GQM process step 5. During collection, data needs to be validated by checking for such things as data completeness, timeliness, and accuracy. Once validated, the data can be presented to the team and other appropriate recipients for interpretation. A key activity of this phase is to store the data in such a way that it facilitates access by the project team and others both during and after a project. Most GQM implementations develop a metric database for this purpose.

Interpretation Phase

After the data is collected, validated and prepared for review, in accordance with the Analysis Plan, the Interpretation

phase involves review of the measurement results by the stakeholders (typically the project team). The team interprets the data in light of the questions asked and the ultimate goals defined. Do the measurement results provide answers to the questions addressed? To what extent has the goal been attained? Typically, during the Interpretation phase the team determines not only the extent to which the actual measurements address their corresponding questions and the extent to which the measurement goals were attained, but also what improvements can be made to the measurement program

itself. Success in this phase is premised on the principle that the measurement program must address the interests of those providing the data and must be based on the project team’s knowledge. These feedback sessions typically lead to

updates to the Measurement and Analysis Plans, and sometimes, to the alteration or addition of measurement goals.

Keep in mind that measurement goals may be related to the product as well as the process or resources. The visibility of information provided by the presentation format of the measurement results makes it easier for the project team to take corrective action during the project, since they are monitoring progress on a periodic basis. They use the quantitative information for fact-based decision-making. Basili includes this analysis and interpretation activity as part of his step 5 of the GQM process.

This phase also addresses making decisions about the preservation of measurement results for use in the future and lessons learned. The GQM team (or persons with overall responsibility for the measurement program) determines how such data should be packaged to provide optimum accessibility and use for future efforts. This activity is consistent with the last step of Basili’s GQM process.

در زندگی بازیهای بسیاری انجام میدهیم ‘ خواه برای سرگرمی و کودکانه ‘ خواه برای سوداگری و سود آوری ‘ یا حتی عاشقانه‘

در زندگی بازیهای بسیاری انجام میدهیم ‘ خواه برای سرگرمی و کودکانه ‘ خواه برای سوداگری و سود آوری ‘ یا حتی عاشقانه‘